Immune checkpoint inhibitors are known as a form of cancer treatment. Researchers at UZH in Switzerland have now identified a new, important function of these inhibitors: promotion of tissue healing. This finding could help advance the treatment of fibrosis and chronic wounds.

The body employs a protective mechanism that curbs overzealous immune responses. Known as checkpoint inhibitors, this system is located on the surface of certain immune cells. Cancer therapy often disables these inhibitors so that the immune system can fight tumour cells more effectively.

Previous observations showed that one of these inhibitors, known as TIGIT, provides a certain level of protection against tissue damage in mice infected with viruses.

“We suspected that TIGIT also has something to do with tissue repair. However, the underlying mechanisms were completely unknown until now,” said Nicole Joller, professor of Immunology at the Department of Quantitative Biomedicine at the University of Zurich (UZH).

Joller’s team recently identified the signalling pathway that TIGIT uses to promote tissue repair.

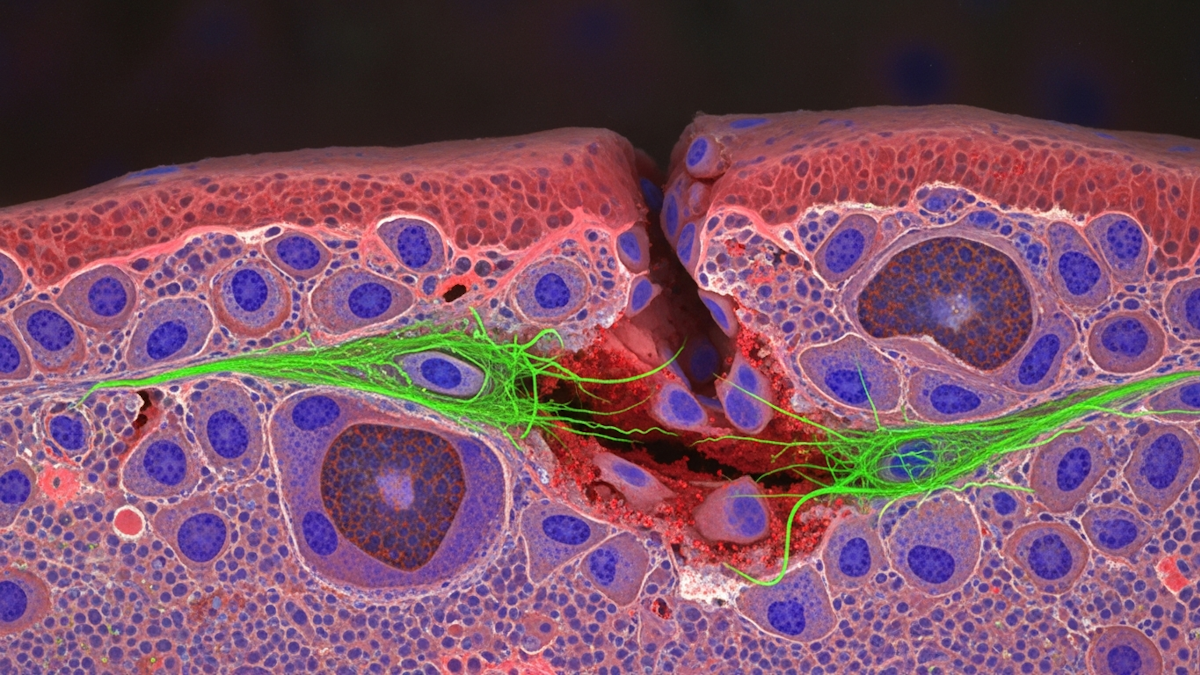

The researchers conducted their investigations using mice infected with the rodent virus LCMV. First, they examined how mice lacking the gene for TIGIT coped with infection. Compared to a control group, they developed more tissue damage, particularly in blood vessel walls and the liver. This finding confirmed that TIGIT plays a key role in preventing this kind of damage.

The team then looked for differences between immune cells with and without TIGIT on their surface. They discovered that only immune cells equipped with the checkpoint inhibitor produced a specific growth factor in response to viral infection. This growth factor activates a multitude of repair mechanisms and is central to tissue regeneration. Further experiments revealed how TIGIT upregulates the gene for this growth factor.

“Our findings show that TIGIT promotes the production of a growth factor in immune cells – one that is critical for repairing tissue after viral infections,” Joller said.

In doing so, her team successfully identified and described a hitherto unknown function of checkpoint inhibitors.

“Our results shed new light on the balance between immune defence and tissue protection,” Joller said.

Her team’s findings could help improve understanding of the tissue-damaging effects of viral infections. It is known that infections such as influenza or COVID-19 can cause severe damage to the body, for instance in blood vessel walls and in the liver and lungs.

Joller also sees promise for innovative treatments of other conditions that affect tissues, such as chronic wounds or liver fibrosis, a disease characterised by scar tissue buildup.

“We could potentially activate the TIGIT checkpoint to accelerate the regenerative process,” Joller said.