Rhabdomyolysis is a condition in which muscle damage—often caused by drug intake—can lead to impaired kidney function and acute kidney failure. However, there have been limitations in directly observing how muscle and kidney damage influence each other simultaneously within the human body.

KAIST researchers have developed a new device that can precisely reproduce such inter-organ interactions in a laboratory setting.

A research team led by Professor Seongyun Jeon of the Department of Mechanical Engineering, in collaboration with Professor Gi-Dong Sim’s team from the same department and Professor Sejoong Kim of Seoul National University Hospital, has developed a biomicrofluidic system that can recreate, in the laboratory, the process by which drug-induced muscle damage leads to kidney injury.

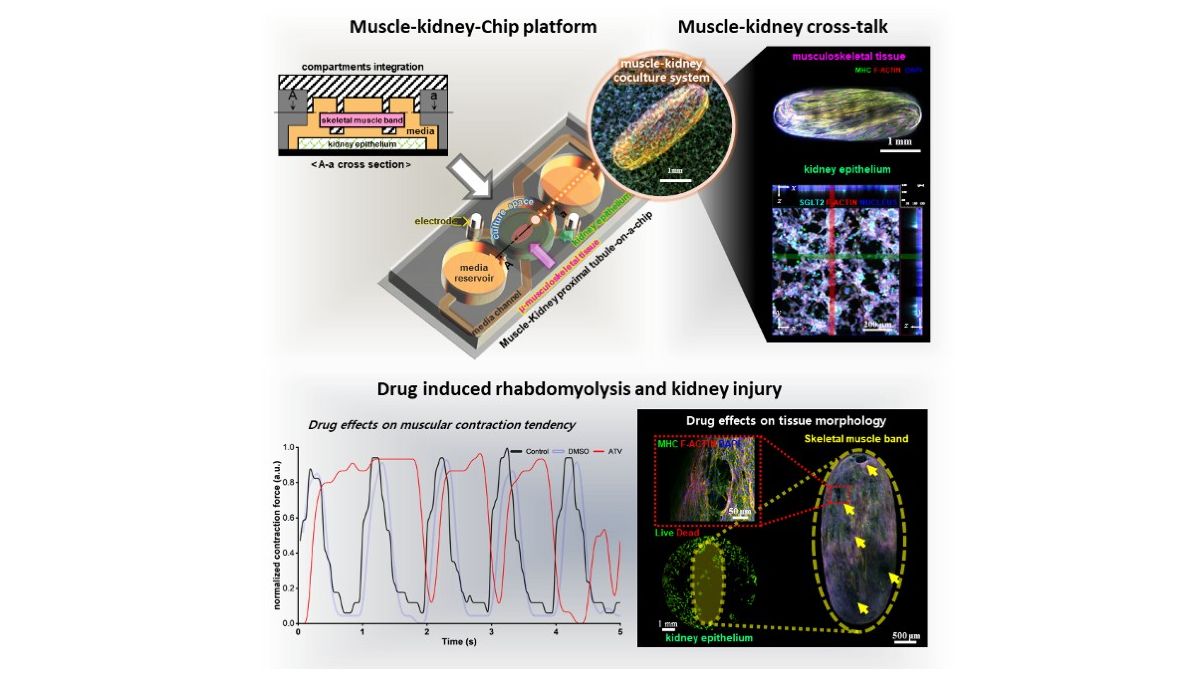

The study is the first to precisely reproduce, in a laboratory environment, the cascade of inter-organ reactions in which drug-induced muscle injury leads to kidney damage, using a modular (assembly-type) organ-on-a-chip platform that allows muscle and kidney tissues to be both connected and separated.

To recreate conditions similar to those in the human body, the research team developed a structure that connects three-dimensionally engineered muscle tissue with proximal tubule epithelial cells (cells that play a key role in kidney function) on a single small chip.

The system is a modular microfluidic chip that allows organ tissues to be connected or disconnected as needed. Cells and tissues are cultured on a small chip in a manner similar to real human organs and are designed to interact with one another.

In this device, muscle and kidney tissues can be cultured separately under their respective optimal conditions and connected only at the time of experimentation to induce inter-organ interactions. After the experiment, the two tissues can be separated again for independent analysis of changes in each organ. A key feature of the system is that it allows quantitative evaluation of the effects of toxic substances released from damaged muscle on kidney tissue.

Using this platform, the researchers applied atorvastatin (a cholesterol-lowering drug) and fenofibrate (a triglyceride-lowering drug), both of which are known clinically to induce muscle damage.

As a result, the muscle tissue on the chip showed reduced contractile force and structural disruption, along with increased levels of biomarkers indicative of muscle damage—such as myoglobin and CK-MM—which are characteristic changes seen in rhabdomyolysis.

Myoglobin is a protein found in muscle cells that stores oxygen and is released into the blood or culture medium when muscle is damaged. CK-MM (creatine kinase-MM) is an enzyme abundant in muscle tissue, with higher levels detected as muscle cell destruction increases.

At the same time, kidney tissue exhibited a decrease in viable cells and an increase in cell death, along with a significant rise in the expression of NGAL, a protein that rapidly increases when kidney cells are damaged, and KIM-1, a protein that becomes highly expressed as kidney cells—particularly proximal tubule cells—are increasingly damaged. NGAL and KIM-1 are biomarkers that increase during acute kidney injury. Notably, the researchers were able to observe the stepwise cascade in which toxic substances released from damaged muscle progressively exacerbated kidney injury.

Seongyun Jeon said: “This study establishes a foundation for analyzing the interactions and toxic responses occurring between muscle and kidney in a manner closely resembling the human body. We expect this platform to enable the early prediction of drug side effects, identification of the causes of acute kidney injury, and further expansion toward personalized drug safety assessment.”