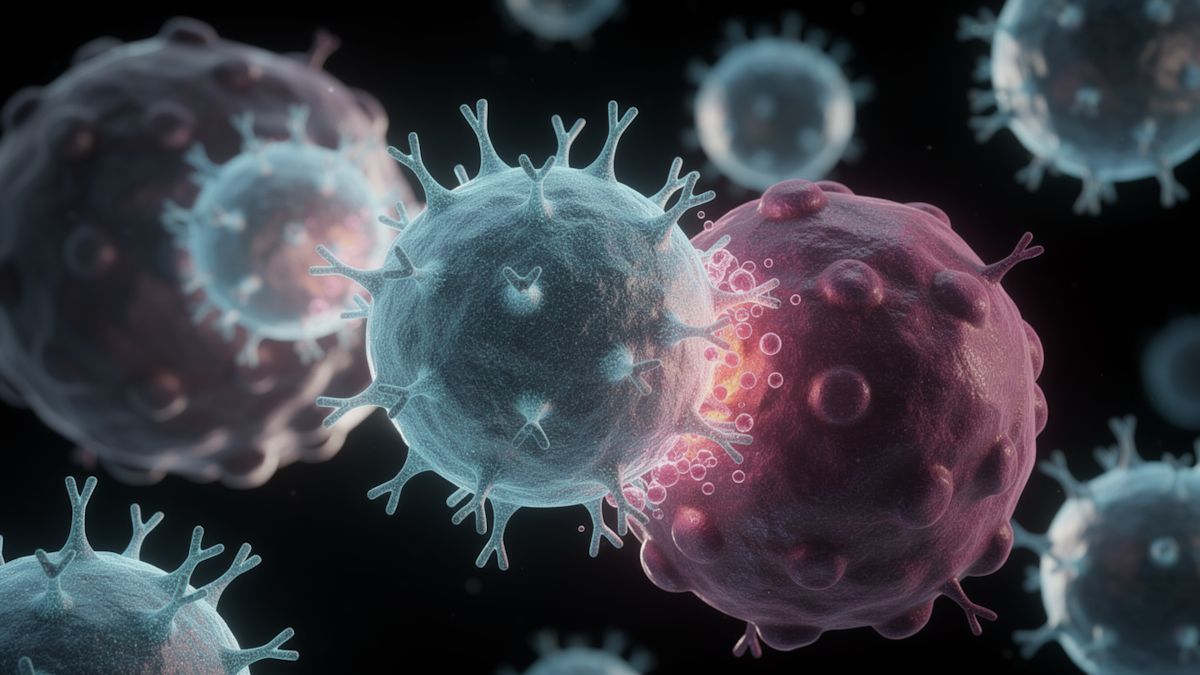

A team led by LMU physician Sebastian Kobold has found a way to allow the body’s immune system to destroy solid tumours.

In 2024, Kobold’s research group at LMU University Hospital had already shown that the metabolite prostaglandin E2 can block T cells – the killer cells of the immune system – in the vicinity of a tumour, so they do not attack cancer cells. This is one of the reasons why therapeutic CAR T cells have lacked success against solid tumours such as bowel or pancreatic cancer.

Now, Kobold’s immunopharmacology team at the Institute of Clinical Pharmacology has turned this discovery to potential practical use, in close cooperation with Jan Böttcher at the University of Tübingen. The researchers modified CAR T cells so that the prostaglandin E2 can no longer bind to them. This allows CAR T cells to destroy solid tumour sites. The new study was recently published in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering.

Using CAR T cells to direct the immune system of a cancer patient against tumour cells, and thus combat the life-threatening disease, often works very well in patients with certain leukaemias (blood cancer) and lymphomas (lymph node cancer). The cancer disappears or at least does not further progress and cause the patient to die.

In modern therapies, T cells can be taken from patients and genetically engineered to produce a certain protein (CD19) on their surface. When these modified CAR T cells are reintroduced into the body, CD19 ensures that the CAR T cells recognize the cancer cells and bind to them with precision. This causes the cancer cells to die.

Unfortunately, solid tumours like bowel, pancreatic, prostate, and lung cancer have developed mechanisms for rendering CAR T cells ineffective.

“However, we are gaining a better understanding of the underlying molecular mechanisms all the time,” Kobold said.

His team has demonstrated, for example, that prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) in the microenvironment suppresses the function of T cells by binding to special receptors on the surface of T cells.

Now the Munich-based researchers and their colleagues have genetically engineered therapeutic CAR T cells that are no longer able to produce these special receptors. As a consequence, PGE2 can no longer bind to the CAR T cells and have its immunosuppressive effect. This was demonstrated in models of breast or pancreatic cancer, where the CAR T cells kept the tumours in check. These CAR T cells proved to be highly effective in tumour samples from human patients with pancreatic or bowel cancer or neuroendocrine tumours.

“Soon it will be possible to test our approach in clinical studies,” said Janina Dörr, lead author of the study.

Initially, this will not involve people with solid tumours, but with lymphomas. Barely half of lymphoma patients have been able to benefit from CAR T therapy to date.

“According to our findings, there is a good chance that therapy with silenced PGE2 will be considerably more successful,” Kobold said.

Should this prove to be the case, a study on patients with solid tumours could follow if suitable funding is found.